The connection between metrics and peformance is well established. The old axiom "what gets measured gets done" is true. What is less clear is whether most firms are tracking the best performance indicators.

The connection between metrics and peformance is well established. The old axiom "what gets measured gets done" is true. What is less clear is whether most firms are tracking the best performance indicators.Monday, December 22, 2008

Are You Measuring the Things That Really Matter?

The connection between metrics and peformance is well established. The old axiom "what gets measured gets done" is true. What is less clear is whether most firms are tracking the best performance indicators.

The connection between metrics and peformance is well established. The old axiom "what gets measured gets done" is true. What is less clear is whether most firms are tracking the best performance indicators.The Myth of Multitasking

Now here's a novel resolution for 2009--do less! Sound preposterous? Generally we charge into the new year with visions of achieving more than we did last year. Getting better results usually translates into doing more. In a weak economy, just holding your own may require working harder than last year.

Now here's a novel resolution for 2009--do less! Sound preposterous? Generally we charge into the new year with visions of achieving more than we did last year. Getting better results usually translates into doing more. In a weak economy, just holding your own may require working harder than last year.Tuesday, December 16, 2008

Don't Waste the Client's Time!

In the midst of a recession, we can expect a significant increase in the number of sales calls as firms scramble to find work. Poor clients! Let's face it, most sales calls are a waste of the client's time. Here are a few of the classic time wasters:

In the midst of a recession, we can expect a significant increase in the number of sales calls as firms scramble to find work. Poor clients! Let's face it, most sales calls are a waste of the client's time. Here are a few of the classic time wasters:- Glad-to-meet-us sales calls. "I'd like to come by and introduce you to our firm. Who knows, you might discover something about us that you haven't seen in all the other firms calling on you."

- Drive-by sales calls. "I'm going to be in your area next week, so since it's convenient for me, I wonder if we could meet."

- Touching base sales calls. "It's been a while since we last met, so I thought it would be a good idea to get together again so, well, you won't forget about us."

- Something's up sales calls. "I know you haven't heard from us for a long time, but I heard the RFP is coming out soon, so I thought it's time we visit again."

Of course, we're never quite so honest in asking for the appointment. But don't you think clients get the message? The sales call is primarily for our benefit, especially now that we really need the work.

In my experience, the average sales call lasts about one hour. That's a substantial chunk of the client's day. And what does the client get in return for spending some of his or her valuable time with us? Let me challenge you to make answering that question foremost in thinking about your next sales calls. Here are some suggestions:

Bring something of value to every sales call. This is what I call your entree, a valid business reason for the client to expend precious time meeting with you. Typically this will involve sharing information or advice relevant to a pressing problem or need. Offer your entree as a basis for scheduling any sales call. Of course, this means you need to do your homework to try to identify what issues the client is facing before making the initial contact.

Make serving the client the focus of the call. Don't treat a sales call with a prospective client much differently than you would a project meeting. You're there to help. There's no need to tell the client about what you can do; demonstrate it by doing what you do best. That's the best way to sell anyway.

Ask for only 20 minutes of the client's time. I know, that's hardly enough time to accomplish much. So you have to come prepared to maximize the time. But here's the beauty of this approach: Rarely will you only be there for 20 minutes. If you're providing value, the client will encourage you to stay longer when you say, "I promised only 20 minutes of your time and that time's up. Is there anything more I can help you with?" It's a great way to show that you're sensitive about the value of the client's time

End each call by establishing the basis for the next meeting. As hard as it may be to identify your entree for the initial sales call, it can be even tougher for subsequent meetings. So a key goal for each sales call is to mutually determine why a next meeting would be beneficial. Of course, this is much easier to accomplish if you've shown that meeting with you is valuable for the client.

Many technical professionals spend too much time trying to convince the client why their firm is a better choice. By respecting the client's time, bringing something of value to every conversation, and demonstrating your commitment to serve the client, you will do more to win approval than any sales pitch can ever accomplish. So before you make that next call to the client, be sure you won't be wasting his or her time.

Monday, December 8, 2008

Level 5 Marketing

Marketing in this business suffers from low expectations. I find this true even among most marketing professionals. In the midst of a recession with the worst still ahead for most A/E firms, perhaps it's time to raise the bar in terms of what we expect our marketing efforts to achieve.

Marketing in this business suffers from low expectations. I find this true even among most marketing professionals. In the midst of a recession with the worst still ahead for most A/E firms, perhaps it's time to raise the bar in terms of what we expect our marketing efforts to achieve.Level 1: We have some materials. You have a brochure, resumes, project descriptions, a website. For some firms, that's about as far as their marketing efforts have taken them. And some struggle even at Level 1. But for firms with a strong client base, sound selling skills, and little ambition to grow much, Level 1 may well suffice.

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Investment Time on the Rise?

The average employee has 79 unbilled days a year. Surprised? That’s based on the industry median utilization of 60%, and doesn’t include vacation, holidays, or sick leave. That means the average 100-person firm has 7,900 days of unbilled time that can be applied to various corporate functions and initiatives (you can do the math to determine what’s available in your firm).

The average employee has 79 unbilled days a year. Surprised? That’s based on the industry median utilization of 60%, and doesn’t include vacation, holidays, or sick leave. That means the average 100-person firm has 7,900 days of unbilled time that can be applied to various corporate functions and initiatives (you can do the math to determine what’s available in your firm). - Eliminate nonproductive time. There is a distinct difference between nonbillable and nonproductive time, although some in our business seem to equate the two. When workload drops, redirect people's time to productive nonbillable tasks. Treat these tasks like projects, with budgets, schedules and accountability.

- Build teams to increase effectiveness. We do projects in teams because they increase productivity and collaboration. Nonbillable tasks generally warrant a team approach as well. Of course, it's important to assign an effective and committed leader to each team. Avoid the mistake of overloading current leaders with too many responsibilities; this is a time to help develop other leaders at various levels.

- Broaden involvement in business development. Since generating new work is a growing concern for most firms in this economy, redirecting nonbillable hours to this function is a likely priority. This doesn't just mean more sales activity. There are many opportunities for people at all levels of your firm to get involved: performing internet research, creating intellectual capital, networking with existing acquaintances, getting marketing resources (e.g., resumes, project descriptions, contact lists, etc.) in order.

For more advice on capitalizing on your investment time, check out my article "Investing Nonbillable Time."

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Improving Your Win Rate

As a performance metric, proposal win rate seems to invite its fair share of skepticism. Some question the reported industry median of 40%, claiming it's skewed and unrealistic. Indeed, part of the problem is inconsistency in how the number is derived. Many firms mix project add-ons and sole source awards into their calculation (it should include only competitive proposals). In my own informal surveys, as well as my experience working with different firms, I find that most fall short of the 40% benchmark. Twenty to thirty percent is more common.

As a performance metric, proposal win rate seems to invite its fair share of skepticism. Some question the reported industry median of 40%, claiming it's skewed and unrealistic. Indeed, part of the problem is inconsistency in how the number is derived. Many firms mix project add-ons and sole source awards into their calculation (it should include only competitive proposals). In my own informal surveys, as well as my experience working with different firms, I find that most fall short of the 40% benchmark. Twenty to thirty percent is more common.- Focus on the client, not your firm. The vast majority of proposals I've seen center on the preparer: "Look at us! Aren't we something special." I recognize that the client usually invites such self-promotion in the RFP. The selection criteria weigh heavily on qualifications and experience. Be responsive, but don't fall into that trap. Demonstrate your qualifications through superior knowledge of the client and the project. Address the client's priorities and concerns (of course, this requires that you did your homework up front). Use personal language--the word "you" is the most persuasive in the English language. Make the client the centerpiece of your proposal, not your firm.

- Make it skimmable. Do you really think client reviewers read your proposal cover to cover? I don't either. They skim, looking for the key information they need to make a decision. Unfortunately, most proposals are not easily skimmable. They require too much reading, too much effort. Put the most important messages in your proposal in skimmable form--bullets, boldface, graphics and photos, short paragraphs, etc. Study USA Today for ideas. Also, it's helpful to know how the client handles your proposal. Which sections are read first? What information is used in the initial screening process? Then construct your proposal (with custom-labeled tabbed dividers) to make it easy to navigate.

Of course, there is much more that I could say on this topic. But grasping the principles outlined above is a good start. For a more comprehensive treatment of the topic, check out my white paper Preparing Winning Proposals. And for strategies once you've made the shortlist, you might find the article "You Made the Shortlist: Now What?" helpful.

Got any other winning strategies you'd like to share? I welcome your ideas!

Monday, November 3, 2008

Management Communications in Tough Times

Even in the best of times, management communications with staff are often problematic. I've conducted and reviewed several employee surveys and have found management-to-staff communication to be among the most commonly identified shortcomings. When a firm faces tough challenges, the need for effective communication is even more crucial. Unfortunately that's when many managers struggle most in this area.

Even in the best of times, management communications with staff are often problematic. I've conducted and reviewed several employee surveys and have found management-to-staff communication to be among the most commonly identified shortcomings. When a firm faces tough challenges, the need for effective communication is even more crucial. Unfortunately that's when many managers struggle most in this area.Experts at Experiences

Pine and his co-author Jim Gilmore award the EXPY each year to the company that they believe best delivers the "branded experience." The award dates back to 1999. It's interesting to note that A/E firms comprise two of the nine winners to date. Other winners include American Girl Place, Geek Squad, The LEGO Company, and Joie de Vivre Hotels.Interestingly, two of our Experience Stager of the Year award winners were A/E firms! In 2005 we gave the EXPY to HOK Sport Venue Event for the great work they have done in creating stadiums that fans perceive as authentic. That was for "what" they did. In 2007 we gave it to TST, Inc., of Fort Collins, CO, for "how" they do their engineering work!

TST--led by president Don Taranto and head of marketing Ed Goodman--created The Engineerium to provide an incredibly different, engaging experience around helping clients realize their dreams ("dreamscaping" they call it)...TST is the shining exemplar of experiences in the A/E industry.

You can learn more about TST's approach in the CENews article "Getting Out of the Commodity Zone." Hopefully that will help inspire you to ask the question: Where can our firm fit in the Experience Economy?

Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Getting Feedback From Clients

The "branded client experience" is consistent and intentional. This requires standards, process, and managed effort. I outlined one proven approach in my last post. The branded experience is also viewed as distinct and valued by the client. The only way to know what the client is thinking is to ask.

The "branded client experience" is consistent and intentional. This requires standards, process, and managed effort. I outlined one proven approach in my last post. The branded experience is also viewed as distinct and valued by the client. The only way to know what the client is thinking is to ask.That's simple, but often ignored, advice. Most A/E firms don't regularly solicit feedback from their clients. I presume they believe they either (1) don't need to or (2) don't care to know. Of course, no one would ever admit to not caring what the client thinks. Yet surveys indicate that clients often feel like their A/E providers don't really care. In fact, PSMJ reports that two-thirds of clients who defect do so because of perceived indifference.

Client surveys also debunk the notion that we can safely assume we understand what our clients want without specifically asking. In conducting such surveys myself, as well as facilitating several "partnering" sessions, I can testify that there are commonly problems about which the A/E firm is unaware. In my mind, no firm will succeed in providing consistently great service (experiences) without a regular program of seeking client feedback.

A critical first step in understanding client expectations comes at project outset, in a process I call "service benchmarking." This involves asking the client specific questions about how you can optimize the working relationship and deliver a great experience. From this information, you define what actions are needed to meet client expectations. Then you need to periodically ask, "How are we doing? What can we do better?"

There are two primary means of collecting feedback from your clients that I suggest:

Ongoing dialogue with the client. This should be your primary method for getting feedback. It involves regular conversations with the client at intervals mutually determined during the benchmarking step, plus a final debriefing at the end of the project or major project phase. This activity is best handled by someone other than the project manager, typically the principal in charge or other senior manager. This person assumes the role of Client Advocate (see below).

Formal client survey. A standardized questionnaire is used primarily for tracking service performance trends across the company. While this is highly recommended, you should not use the formal survey as the primary means of gathering client-specific feedback. It's too impersonal for that purpose (although the Client Advocate can personally administer the survey, which makes it more personal and responsive).

The Client Advocate's Role

Many firms assume that their PMs can adequately monitor client satisfaction. But even the most diligent PMs can be sorely mistaken about their client's perception of their performance. Clients are often reluctant to voice their unhappiness to the PM, especially if the PM is perceived to be part of the problem.

That's why I advocate assigning to every key client relationship a Client Advocate. Preferably this is someone who is not directly involved in the project work (except potentially in an advisory or oversight role). Otherwise they lose some of the objectivity and independence needed to function effectively as Client Advocate. This person's responsibilities include:

Monitors client satisfaction. Keeps in touch with the client from time to time (as mutually agreed upon), checking to see that the client remains fully satisfied with the firm's performance.

Ensures responsiveness. Acts as an in-house advocate for the client, seeing that the firm is fully responsive to client needs and expectations.

Acts as third-party liaison. Serves as he point of contact when the client has a problem or concern that he or she prefers not to discuss with the PM, isn't getting an adequate response from the PM.

Conducts the periodic formal survey. Administers the formal survey and follows up to see that the firm responds to client concerns or suggestions that are uncovered in the survey.

The Formal Survey

Following are some suggestions for maximizing the success of the formal survey as part of your process for gathering client feedback:

Define appropriate interval. Either annually or biannually is recommended. The proper frequency will be guided in part by the nature of both the project and your relationship with the client.

Solicit the client's involvement in advance. Explain the purpose of the survey, its value to both parties, and the minimal time involved on the client's part. For long-term clients, request their ongoing participation.

Distribute the questionnaire electronically. Doing the survey in person or over the phone obviously has advantages. But I'm assuming your Client Advocate has already been talking to the client. The formal survey serves a different purpose and is more easily distributed by email—either as an attachment or with a link to a secure web site (SurveyMonkey.com is an excellent resource). Filling out the survey should be hassle free, requiring no more than about 10 minutes of the client's time.

Contact non-responders. Request responses within a week, then have the Client Advocate call or email to ask if the client received the survey (a not-so-subtle but friendly reminder). This will significantly improve your response rate. Remember, you've already had the client agree to participate.

Address problems promptly. When client concerns or complaints are uncovered (and undoubtedly this will happen from time to time), you need to respond promptly and appropriately. In fact, you should define the process for addressing client concerns before sending out the survey.

Share the results with your clients. A great way to demonstrate your commitment to great client service is to send a summary of the survey results to those clients who participated. Include in that summary the actions your firm plans to take to improve service.

For a questionnaire to use for this purpose, check out this one on my website. I developed it jointly with PSMJ and have used it with good results for several years.

How to Get Started

This best feedback will come from clients who are: (1) convinced that your firm is indeed committed to client service improvement and (2) are willing to actively help your firm improve. These are clients who recognize the value of a strong working relationship and are willing to invest a little of their time in making it happen. Don't expect all your clients to participate. But take steps to engage those who will.

Start with your best clients. The best way to generate momentum for this process is to start with those clients who have a mutual interest in strengthening the working relationship. Pick an easily manageable number of clients to start, where you're confident you can be fully responsive to whatever feedback you receive. Then expand to other clients when you're ready.

Build accountability into the process. Make sure your Client Advocates are fulfilling their roles, keeping in touch with the client, promptly responding to any client concerns, and seeing that the project team is meeting expectations. Anything less and the process will quickly lose credibility with both your clients and your employees.

Communicate client feedback to your staff. Everyone in your firm should be engaged in continually improving service and striving to deliver the branded experience. Feedback from clients is the fuel that keeps the fires of continuous improvement burning. Give all employees a stake in helping your firm become a service leader. Share feedback, lessons learned, and success stories.

Wednesday, October 15, 2008

The Experience Trumps Expertise

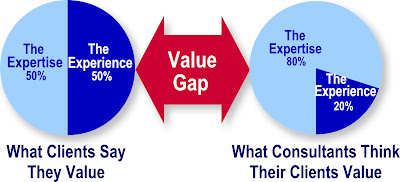

As reported in their book Clientship, authors Kennedy and Greenberg asked over 500 clients this question: "If you consider that we provide you value in two ways and that together they equal 100%, how would you divide up the value between our technical skills (what we do) and our client-service skills (how we do it)?" The prevailing response was 50/50. Another way to put it is that the experience is every bit as valuable to the client as the expertise. Research within our industry by BTI Consulting and Roger Pickar came to similar conclusions.

Could these data be understating the value of the experience? I think so. Consider when your firm has lost clients. Was it because of technical shortcomings or inadequate service? When I've asked that question of principals and managers in our business, they overwhelmingly agree that it's service-related problems (70 to 90% of the time). So we get it. Right?

Not so fast, my friend. BTI asked firms to identify their primary competitive advantage. Eighty percent said it was their technical capability. Only 20% said it was their client service. We clearly place more emphasis on technical excellence than on service excellence (i.e., the client experience). That bias is evident in our business development strategies, our proposals, and our marketing materials. It's evident in the disproportionate amount of time and money we invest in technical improvement versus service improvement.

Our priorities are out of step with those of our clients. There is a substantial gap between what our clients value and what we think they value. And that gap represents an exciting opportunity to distinguish our firms. Indeed, I believe that closing that gap is the best differentiation strategy available to most A/E firms.

So where do you begin? That's the subject of upcoming posts. Next up: The prized product of the Experience Economy is what is commonly referred to as the branded experience. What is it and how do you create it? Stay tuned.

Thursday, October 2, 2008

Responding to the Financial Crisis

The languishing economy took a frightening turn last week with the implosion of the financial markets. As Congress scrambles to pass a rescue bill, many economists are predicting that the worst is yet to come. For most of us, this is the greatest economic uncertainty we have faced in our lifetimes.

The languishing economy took a frightening turn last week with the implosion of the financial markets. As Congress scrambles to pass a rescue bill, many economists are predicting that the worst is yet to come. For most of us, this is the greatest economic uncertainty we have faced in our lifetimes.- Stay close to your clients. Keep informed about how the crisis is affecting them. Look for opportunities to help, even if it involves meeting needs outside your normal scope of services. Subcontract additional expertise if you need it, or make referrals. The point is to make yourself as indispensable as possible. Become the trusted advisor. And, of course, make sure you keep service levels high.

- Reactivate your network. Relationships are critical in uncertain times. If you're like most who have neglected their network, this is a good time to renew your commitment to keeping in touch. Make serving others the primary objective in reconnecting. Offer information, advice, referrals--simple encouragement may suffice! Networking has always been a key growth strategy. Now it may serve as your safety net.

- Keep communication flowing with employees. Undoubtedly recent events have increased anxiety in your organization, especially if your business isn't doing particularly well. It's important to keep employees informed, or better still, engage them in helping address the emerging challenges. Organize brainstorming sessions to come up with ideas to increase service, improve efficiency, explore new opportunities. Transparency is always recommended, but don't overwhelm with bad news. Spend more time talking about the positive changes the company is undertaking.

- Step up business development efforts. If you're cutting costs, don't start here, as many firms are prone to do. Most companies have much room for improvement in how they develop new business. The current economic climate can provide the needed incentive to finally make some real headway. This is a good time to better organize your sales effort. For advice on how to do this, check out this previous post.

- Be diligent in managing cash flow. Poor collections have been a persistent problem in our industry, with receivables averaging over 70 days. Add to that the failure to get invoices out in a timely fashion. Consequently, many firms are forced to borrow to make payroll at times. Such loans may become more difficult to obtain. So now is the time to improve your firm's cash flow management. Obviously, many clients are also facing financial challenges, so collections will be more problematic for some. That's all the more reason to get serious about it.

None of these suggestions are novel. You've heard them before. The point is that uncertain times call for getting back to those things you can count on. Has your firm been neglecting any of the above? This would be a good time build on the good business practice foundations that will help your firm weather the storm that appears to be brewing on the horizon (or may have already arrived for your business).

Friday, September 26, 2008

Diagnosing the Gap

Lack of differentiation. Fundamentally, it's the problem of the undifferentiated product. When clients have more options and see fewer differences between providers, commoditization inevitably sets in. It's a buyers market; they have the leverage and usually exercise it. And providers wind up feeling less appreciated. This trend is a natural phase in the product/service life cycle.

But what about other professionals? Aren't they subject to the same laws of supply and demand? Yes, they are. And other professions are complaining about many of the same challenges that we are facing. But they also have a few advantages that we don't (as I'll explain below).

Charging by the hour. Another factor that has contributed to this problem is our historic tendency to charge by the hour rather than on the basis of the value delivered. No doubt what we do is vitally important to society. But when we sell solutions in hourly increments it invites clients to try to squeeze out the same results (or adequate results) in fewer hours. True, we're moving increasingly to lump sum contracts, but the old stigma remains.

Greater willingness to negotiate price. Other professionals also seem less prone to negotiate down their price. Undoubtedly one reason we're feeling increased pricing pressure is that clients have learned how quickly many firms cave when asked to lower prices. Many A/E firm principals believe this practice is unavoidable if they want the work. But the best way to address client cost concerns is to negotiate scope, not price. Price establishes a sense of value. If we're willing to lower prices it suggests that we're not convinced our value matches the asking price.Failure to adequately address strategic needs. One big advantage that many professionals have over us is that they help clients address their strategic needs. We tend to focus almost exclusively on technical needs. Strategic needs are those that affect the overall success of the client organization. They commonly relate to financial, competitive, political, or operational factors. Of course, our projects help meet strategic needs. But we often fail to make the connection. As a result, other professional firms have taken over some of the big-think, planning-oriented strategic roles that A/E firms used to fill.

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

What's Wrong With This Picture?

Architecture and engineering are among the most respected professions. But they are not among the most valued. Why would I say that? Consider the following evidence:

Architecture and engineering are among the most respected professions. But they are not among the most valued. Why would I say that? Consider the following evidence:- A/E firms have a labor multiplier well below that of other professional firms, such as attorneys, accountants, management consultants, and advertising agencies. The median in our industry is 3.0 compared to 5.0 for other professionals. The mark-up on labor costs is certainly one measure of perceived value.

- Not surprisingly, A/E firms are among the least profitable of all professional service sectors. According to BizStats.com, only employment services and travel arrangement and reservation services have lower profit rates. Even administrative support services have higher profits!

- Price competitions obviously contribute to lower profits. One survey found that 68% of A/E firms had participated in procurements where cost was the primary selection criterion. Imagine what it might be if we didn't have Qualifications-Based Selection rules in place.

- Our clients are also less loyal than in other professions. A study by RainToday.com found that 88% of A/E firm clients were open to changing their current providers, the highest percentage among the professional service sectors they investigated.

- Several client surveys concur that clients see little real differentiation among firms in our industry.

These facts lend credibility to the growing sense among us that our business is becoming increasingly commoditized. This was a pervasive concern even before the economic downturn. In an environment of tighter funding and more scrutinized spending, we can expect to have to work even harder to deliver distinctive value.

Why are our services less valued than those of other professions? I don't have any ready answers, but I do have some reasonable theories. In subsequent posts, I plan to outline what I believe to be at least a big part of the problem, and what we can do about it. I hope you will contribute to the discussion.

Thursday, September 18, 2008

Well, Duh!

Sometimes we fail to do the obvious things that would improve our chances of success. I'm certainly guilty of that. How about you? Maybe we haven't had the "Aha!" moment when it suddenly becomes clear what we should have been doing all along. Other times the better way is staring us in the face and we still don't act on it for whatever reason.

Sometimes we fail to do the obvious things that would improve our chances of success. I'm certainly guilty of that. How about you? Maybe we haven't had the "Aha!" moment when it suddenly becomes clear what we should have been doing all along. Other times the better way is staring us in the face and we still don't act on it for whatever reason.I was reminded of this yesterday as I delivered a couple of sessions at the Virginia Engineers Conference. One dealt with time management, the other was on persuasive communication. As I often do, I occasionally asked for a show of hands to see how many people or firms were doing the things I recommended. These included:

- Planning one's activities for the week. Only about a third of my audience indicated that they took a little time at the start of the week to identify priorities and schedule activities. No wonder so many find themselves in the throes of "fighting fires" day in and day out. Stephen Covey's research found that the average corporation spends about 75-90% percent of its time on urgent activities, most of which are not considered important.

- Managing non-billable time. Less than a fourth of attendees indicated that their companies "manage" the non-billable hours spent on activities such as business development or corporate initiatives. By manage, I mean determining the level of effort required, assigning people specific tasks, budgeting their time, and tracking how much time is actually spent. Billable hours, of course, receive this kind of attention. Why not the "investment time" critical to a firm's success?

- Making documents skimmable. While everyone seemed to agree that their proposals and reports were probably skimmed rather than read by their target audiences, no one indicated that their firm designed documents to make them more skimmable! This is an obvious opportunity to set our proposals apart. Using second person in proposals. Once again, no one raised their hand when I asked how many used the word "you" in their proposals (this was an audience of about 75 people!). This despite the fact that several studies over the last 30 years have reached the same conclusion: You is the most persuasive word in the English language. Why then is it banished from our most important persuasive documents?

- Including an executive summary in proposals. Very few indicated they did this, something that I've routinely done for many years. I recognize that RFPs rarely ask for one, so the obviousness of this strategy may not seem apparent. But one large study found that executives read 100% of summaries in reports and similar documents (that's why they're called "executive summaries"), while only 10% read the body of the documents. Does this apply to proposals? I can't prove it, but will point to my 75% win rate as evidence that it at least seems to work.

- Regularly soliciting feedback from clients. Everyone claims to provide great service to their clients, but only about a fourth of firms routinely ask clients how well they're doing, based on my informal survey. A major study by Accenture of service leaders across different industries found that they consistently do two things: (1) relentlessly manage the service delivery process (something rarely done in our industry!) and (2) routinely solicit feedback from customers.

There are undoubtedly many other obvious things we should be doing; these are just a few that came up in my presentations yesterday. It might be fun to compile a "Well, duh!" list of strategies that are inexplicably ignored in our business. Any you'd like to contribute?

Thursday, September 11, 2008

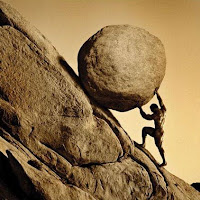

The Hard Work of Real Change

If there's one thing that characterizes leadership, it's the ability to affect positive change. We laud leaders who are visionary and inspirational, but ultimately what counts is what gets done. Here's where the old Woody Allen quote, "90% of success is just showing up," comes into play. Leading change is certainly a complex endeavor, but the first requirement for firm leaders is simply showing up. By that, I mean committing to the hard work over the long term to see change take root. The lack of this kind of management commitment, in my experience, is the number one reason change efforts fail (and the vast majority do).

If there's one thing that characterizes leadership, it's the ability to affect positive change. We laud leaders who are visionary and inspirational, but ultimately what counts is what gets done. Here's where the old Woody Allen quote, "90% of success is just showing up," comes into play. Leading change is certainly a complex endeavor, but the first requirement for firm leaders is simply showing up. By that, I mean committing to the hard work over the long term to see change take root. The lack of this kind of management commitment, in my experience, is the number one reason change efforts fail (and the vast majority do).- Training events

- New policies or procedures

- New assignments or positions

- Reorganization

- New technology

Unfortunately these tactics rarely, if ever, work. Not on their own, anyway. That's because real change doesn't take place in outward forms; it requires inward transitions. In other words, corporate change doesn't happen until individual change does. And that takes time, longer than many firm managers are willing or able to commit to.

I learned this firsthand as a manager. We had several change efforts going (too many, I'm sure). So when I felt we had made significant progress on one to shift my attention elsewhere, I'd soon discover we were backtracking where I thought we had reached a beachhead. I was repeatedly surprised to learn how much I needed to keep pushing to keep change going. You might call it the Sisyphus Principle, where the weight of doing things the old way is constantly threatening to undo the progress you've made--until the transformation has been internalized.

Leading that transformation requires more than smarts and starts. It demands hard work and endurance over the long haul. I've worked with a lot of companies that valued my experience and ideas to help them change and improve. But few have been able or willing to make the investment of management time and attention that was really needed. These firm leaders didn't necessarily lack the ability, just the availability. I've learned a lot about leading change efforts, but I've yet to discover any shortcuts.

So what should you take from this? First, set realistic expectations. If reaching your goals is important, consider how much effort is really needed. Then determine if you can commit that much time and attention to it. If not, scale back your goals. False ascents up the mountain of change not only fall short of the goal, but discourage people from committing to future change efforts.

Second, carefully budget time and attention. There's a limited supply. Firm leaders commonly over-commit then under-achieve when it comes to change. Manage change initiatives like projects, defining the tasks, manpower, time, and money needed to get the job done. Don't double-book. Whatever is committed to a specific change effort should be off-loaded somewhere else. Remember people are already suffering from mental overload. To keep the desired change at the forefront of their minds, you have to keep it constantly in the corporate conversation.

Finally, don't make promises you can't (or won't) keep. This is a matter of your integrity and credibility. Without it, you can never build the trust necessary to guide people through the transformation. In the end, trust is the bedrock on which sustained change must be built.

Friday, August 29, 2008

Natural Selection vs. Intelligent Design

No, I'm not getting into that controversy (not in this space, at least). Instead I'd like to briefly explore the genesis of corporate cultures. It's apparent that some firm cultures are the result of intentional design. Others seem to have evolved more or less accidentally, the product of mostly unconnected, random circumstances. Most firm cultures probably fall somewhere in between, but more towards the "natural selection" model.

No, I'm not getting into that controversy (not in this space, at least). Instead I'd like to briefly explore the genesis of corporate cultures. It's apparent that some firm cultures are the result of intentional design. Others seem to have evolved more or less accidentally, the product of mostly unconnected, random circumstances. Most firm cultures probably fall somewhere in between, but more towards the "natural selection" model. - Their revenue grew more than 4x faster

- Their rate of job creation was 7x higher

- Their stock price grew 12x faster

- Their profit performance was 750% higher

Other studies have reached similar conclusions. That's not surprising when you consider the prevailing definition of corporate culture. It is the "sum of values, habits, and rules that influence how things get done within the organization." In a strong culture, everything is aligned towards greater proficiency in getting things done. That's not to suggest mere efficiency and productivity. Strong cultures are rooted in a core ideology that lends not only to doing things right, but doing the right things.

Here's my thesis: Cultures that have evolved by natural selection are to some degree dysfunctional because they lack alignment of "values, habits, and rules." Make no mistake, some are still successful. Consultant David Maister contrasts two cultural models among professional service firms: (1) the "one-firm firms" and (2) "warlord firms" (love that description!). Warlord firms are built around individual entrepreneurs who loosely collaborate but generally build their own domains of practice. When these individuals are highly talented, the firm can prosper--but there's usually a cost.

Warlord firms tend to be inefficient, slower to adapt to market changes, prone to internal conflict, and less effective in developing junior staff. These cultures are often exposed when there's a downturn or other change and a coordinated corporate shift in strategy is needed. Warlord firms are also notorious for divergent levels of client service, since shared values and practices are much more difficult to achieve.

One-firm firms, by contrast, are characterized by their alignment around shared values and practices. These firms are clearly the product of deliberate design and dogged effort because such community is reached only by paddling against the current of natural organizational entropy. Yet in that type of culture basic human needs are met, and this is the secret of their enduring success. People are generally more productive when they work within a principled, collaborative, structured, and nurturing environment.

There's another important facet of culture to mention here. Corporate culture is a composite of both formal and informal systems. Formal systems include strategy, policies, and procedures. Informal systems include values, attitudes, and habits. When the two are not aligned, the informal systems always trump the formal ones. That's why most strategy fails. It prescribes a new direction without doing the hard work of changing persistent values, attitudes, and habits. Thus it succumbs to the process of natural selection.

So with that background, let me suggest a few steps to creating a stronger corporate culture. You can read more about this in the article "Cultivating a Strong Company Culture" on my website.

- Assess your current culture

- Fortify your company values

- Align strategy with your culture, or visa verse

- Commit to regular communication

- Take steps to promote a sense of community

- Hire for cultural fit (this is critical!)

Particularly if your business is down, this might be an appropriate time to consider your firm culture. Does it reflect the kind of company you want to have? Does it position you for sustainable success? Are there shared values that guide all corporate behavior? If not, what changes are needed? Answering these questions may be far more crucial to your future than usual substance of our strategic plans and actions.

Monday, August 25, 2008

Escaping the Activity Trap

The Activity Trap is a common occupational hazard in our business. You've undoubtedly been impaired by it and some of you are routinely entangled in it. It's a serious problem, costing us clients, profits, and peace of mind.

The Activity Trap is a common occupational hazard in our business. You've undoubtedly been impaired by it and some of you are routinely entangled in it. It's a serious problem, costing us clients, profits, and peace of mind.So what is it? The Activity Trap is what happens when we get so caught up in the busyness of doing tasks that we lose sight of the desired outcomes. Obviously, inadequate planning is a root cause. In my experience, poor project planning is a notorious shortcoming in our profession.

But the problem of the Activity Trap runs deeper than merely shortchanging an important step of the project delivery process. It has to do with prevalent mindsets in our ranks. Most engineers are inclined to view projects as a list of tasks to be done, giving too little focus to what they ultimately need to achieve. Most architects do a better job of thinking about outcomes but are prone to neglecting the work process, so they too fall in the Activity Trap.

I know these are stereotypes and not everyone fits the characterization. But the patterns are common enough to be problematic. What are some of the costs of the Activity Trap?

- Start with rework, which according to best estimates constitutes 15-25% of our project budgets. The most common cause, according to one study, is improper sequencing of work tasks (i.e., poor planning).

- Productivity in the AEC industry lags behind almost every other business sector. We have actually lost productivity over the last 30 years while other non-farm businesses have realized huge productivity gains. Suspected reasons: Poor planning and inefficient work processes.

- According to PSMJ, the most common cause of project-related problems is inadequate planning. These problems result in financial losses, increased liability exposure, and unhappy (and often lost) clients.

- In my own consulting experience, the primary source of stress and conflict in our offices is clumsily executed projects, most of which can be directly attributed to the impact of the Activity Trap.

To say we need to do better at project planning seems too obvious an answer. The problem, however, is not so easily solved. We all acknowledge that planning is important. So why don't we do more of it when it's so apparent it's needed?

I suggest we need to get back to the basics of client focus, problem solving, and leadership. Clients don't hire us to do tasks, they want us to deliver value and solutions. They want us to understand their problems in broader perspective than just our expertise. They face strategic, economic, operational, and political needs that should demand our attention and force us out of the usual default task execution. And they expect our project managers and principals to supply the kind of leadership that transforms our task-oriented culture to one driven by service and value.

But first we need to take an inventory the real impacts of the Activity Trap. That may well motivate us to then figure out how to free ourselves from it.

Friday, August 22, 2008

The Five Rs of Superior Service

But there are some basic principles of great service that are pretty consistent from client to client. These are what I call the Five Rs of Superior Service. Do these well and you'll go a long way towards distinguishing yourself as a "super server."

Reachability

Definition: Obviously a coined word (hey, I needed an “R”) referring to how easy it is for the client to contact you.

Illustration: When your client has a problem or question, you can assume that he wants to be able to reach you immediately. That may be impossible, but there are steps you can take to increase your reachability:

- Make a promise to return client calls within a specific time frame (e.g., 3 hours)

- Regularly update your voicemail greeting to include your whereabouts

- Always let the receptionist know where you are and whether you can be reached

- Have backups assigned to field questions when you are unavailable

- In some cases, offer to wear a pager for more immediate accessibility

Application: This is probably the easiest of the Five Rs to excel at. But based on my experience in calling my clients and colleagues, there’s much room for improvement (at least relative to the second and third bullets). The suggestions above are a good start, but ask your client specifically how he would like you to make yourself more reachable. This might be delineated in a written client service plan.

Responsiveness

Definition: This refers to your willingness to adapt to meet your client’s changing needs.

Illustration: Most technical professionals work hard at being responsive. They readily agree to scope changes, alter schedules and shift resources, and put in long hours to accommodate their clients. But the focus is on what I call “situational responsiveness.” We often refer to this condition as “fighting fires.” Fewer firms go beyond this kind of responsiveness to make systematic changes in response to client needs and expectations—what we’ll call “systematic responsiveness.” This involves proactive and long-term adaptations to better serve clients, such as changes in work processes, systems, and policies that are client-driven.

Application: A commitment to superior service should move your firm towards improving your systematic responsiveness. This enables a consistent level of service across your organization. This will involve actions such as the following:

- Systematically uncover client expectations that go beyond the technical scope of work (i.e., service benchmarking)

- Develop "service deliverables," converting service delivery into a set of tasks that can be managed, budgeted, and scheduled like technical work activities

- Seek regular client feedback leading to continuous improvement of project delivery and client service practices

- Ensure that invoices and project accounting practices align with the client's accounting system

Reliability

Definition: Reliability is the quality of trustworthiness that you demonstrate to your clients.

Illustration: Do you consistently meet client requirements and expectations? Do you always follow through on your commitments? For example, if you often extend client deadlines, even with the client’s approval, you are not proving yourself reliable. Your reliability defines the level of trust in your relationship with the client. Without it, you cannot deliver added value. Some ways to enhance the client’s perception of your reliability include:

- Avoid making commitments that you doubt you can meet, even when the client wants it

- Treat all missed targets and mistakes as service breakdowns, even if the client appears to be okay with it

- Follow a standard, careful process for assuring the quality of all client deliverables

- Communicate on a proactive, regular basis with your client

- Offer service guarantees to your clients (these need not be terribly risky to be effective)

Application: Consistent processes and standards are an effective way to improve reliability. But resist the temptation to go too far in this respect, which can stifle creativity and responsiveness. The best way to get buy-in is to allow staff to actively participate in defining the processes that can achieve client- and management-defined standards.

Recovery

Definition: Recovery refers to the actions taken in response to a service breakdown.

Illustration: No matter how diligent you are, you will occasionally experience a service breakdown—a design error, a missed deadline, a budget overrun, a misunderstanding. This is a critical juncture in the client relationship. Failure to respond appropriately may cost you the client’s trust, and ultimately their business. But a well executed recovery can actually strengthen the relationship.

Application: The following steps typically are key to effective recovery from a service breakdown:

- Take responsibility for the problem. This doesn't mean you necessarily have to take the blame. Sometimes service breakdowns result from circumstances beyond your control. But if it's your fault, admit it. Don't make excuses; that only makes the situation worse. Even if it's not your fault, let the client know that you will take responsibility for trying to resolve it.

- Make a commitment to correct the problem. You should, of course, determine what the client desires or expects you to do to fix it. It's wise to try to understand the implications of the problem from the client's perspective. Ask about how it specifically impacts them. Then suggest an appropriate plan for addressing the problem to the client's satisfaction. And commit to follow through.

- Take steps to prevent it from happening again. This demonstrates your commitment to continuous learning and improvement, which is at the heart of true responsiveness. As mentioned earlier, simply fixing the problem (situational responsiveness) is important. But taking steps to prevent it from recurring (systematic responsiveness) is where you can really show your devotion to delivering superior service.

Obviously, there may be serious liability concerns associated with service breakdowns, which can place limits on your recovery. Keep in mind, however, that satisfying your clients is one of the best risk management strategies available.

Relationship

Definition: Your relationship with the client is not simply a contractual obligation to provide a scope of services or work products. Indeed, the interaction between the two parties should be part of the value delivered. The best business relationships are characterized by the qualities of trust and mutuality.

Application: A good relationship with the client facilitates superior service delivery, and great service strengthens the relationship. Service is not an impersonal product like studies or designs. There are no defined codes or "standards of care" for service. It must be delineated and delivered at the personal, subjective level in the context of relationship. This lack of concrete objectivity may foil many technical professionals who often find clients an impediment to "just doing the work." But those who push the client relationship to the forefront are those who truly excel in this business.